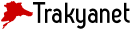

Important for its mineral resources as well as its rich forest potential, Thrace was a hub of interest and activity for foreign tribes, nations, and the most important powers of antiquity, both from the East and West, as well as for the tribes settled there. Interested in the Greek city-states from the West and the Persians from the East, the Thracian lands were also valued by the Macedonians and Romans. Furthermore, Scythians from the North and Celts from Central Europe also had significant influence in Thrace. Vize and Demirköy, located at the foothills of the Istranca Mountains, are located in the heart of the inland areas abandoned to the Thracians, outside the areas of Greek and other foreign domination and influence generally seen in the south of present-day Eastern Thrace and along the Evros River. Therefore, it is certain that they were an important Thracian center in the pre-Roman period. The numerous tumuli and other archaeological evidence found around the Istranca Mountains attest to this. However, due to the lack of a written history of the Thracians, it is virtually impossible to find much historical data about these periods.

To provide a general overview of Thracian history and, with available information, determine the role of the Astai (Ast) in this process, it is necessary to examine the general history of the Thracians. Whether the Thracians were an indigenous culture derived from and developed from earlier Neolithic cultures, or whether they were formed by the movement of tribes whose origins extended to the Dnieper and Diniester rivers or the Carpathian region, and from there migrated southward, is a matter of considerable debate. However, one certainty is that the use of bronze and later iron tools, the importance of mining within Thracian culture, and the veneration of fire, which are among the defining cultural characteristics of the Thracians, indicate that their origins lie in the Late Bronze Age and the European Iron Age, and that the Thracian culture and way of life took shape during the Iron Age. The Thracians likely took shape after the end of the Bronze Age, around 1000 BC, in connection with the region's mineral wealth. They acquired their lifestyle and cultural characteristics, known as a blend of new waves of migration from the north and a life based on local understandings. Although the first data on the Thracians date back to the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, Homer's Iliad mentions the Thracians as allies of Troy, settling in northwestern Anatolia and probably the Marmara coast of Thrace and the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Between 1000 and 800 BC, the Thracians appear to have formed tribes under the leadership of chiefs who were also high priests. Orpheus, who played a prominent role in ancient mythology, is widely rumored to have been a priest and tribal chief during this period. The tribes that lived during this period, particularly with tombs and open-air temples integrated into dolmen-type monuments, were dispersed throughout the mountainous regions of Thrace.

With the settlement of Greek colonies along the Aegean coast in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, a social system emerged in Thrace consisting of tribal confederations, large landowners, and peasants tied to their land. A vibrant trade network developed between the Thracians, represented by the numerous tribes whose names are known from Greek sources, and the Greek colonies along the coast. The Thracians exported products such as wood, coal, mineral salt, and fish, while importing ceramics, metalware, luxury goods, olive oil, and wine from the Greeks. It appears that the Thracian tribes were not completely settled in one place and occasionally moved. During this period, the presence of the Astai (Ast) tribe, along with the Tyns in İğneada and Midye (around Kıyıköy), and a tribe affiliated with them, the Tranipsas, has been identified in the foothills and north of the Istranca Mountains. Above the Tyns, there were the Melandites. 8th-7th centuries BC The Bithyns, who migrated to Anatolia in the 10th century and established a state there, also had relations with the Tyns.

Between Persian campaigns against the Scythians and later against Greek cities in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, the Persians established their dominance over Thrace. The Skyrmians and Nipsians are generally mentioned among the tribes that established good relations with the Thracian tribes and accepted Persian rule. Of these tribes, the Nipsians were located in the northernmost part of the Strandja Mountains. Among these tribes, the Asts are not mentioned by Herodotus. It is likely that the Nipsians played an active role in the region during this period.

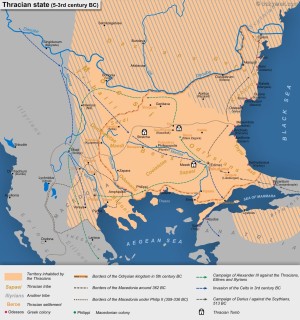

In the 5th century BC, conflicts and wars broke out between Athenian and Thracian tribes over mineral deposits. The 5th century BC saw the establishment of a Thracian Kingdom under the rule of the Odrysians, who settled in the Meriç basin. The state, formed under the leadership of the Odrysian chieftain Teres (460-440 BC), essentially adopted the Persian system of administration. Within this system, shaped around rulers who declared allegiance to the central government, small farmers lived around the rulers' estates. The Thracian people joined the army as infantry, while rulers and distinguished nobles served as cavalry. Tribes residing in the Meriç and Ergene plains were responsible for providing soldiers to this army. Tribes further west were independent.

We learn that, between the 5th and 4th centuries BC, a delegation was sent from Athens, accompanied by the Odrysian King Stalkes, to the Subaltern King Tereus in Vize (Bizye). This demonstrates the existence of a powerful Subaltern State in Eastern Thrace at this time.

In the 4th century, the Macedonians began advancing into Thracian territory. First, King Philip II (359-336 BC) and his son Alexander the Great (386-323 BC) fought significant wars with the Thracians, dominating the region. After Alexander's death, one of his generals, Lysimachus (323-281), became ruler of Thrace. Despite the partial successes of Seuthes III, Lysimachus established his rule in 305 BC. However, with his death in 281, the Thracian tribes became completely independent.

In the 3rd century BC, the Celts began invading Thracian lands from the west, crossing Thrace from end to end, and advancing as far as Byzantium. (279 BC) The Celts established a state centered in the western part of Eastern Thrace, around the Odrysian lands. This city-state, which lasted about 60 years, was destroyed by the Thracians. Local Thracian states were established in its place. All foreign invasions and raids failed to eradicate Thracian independence and cultural identity.

In the 2nd century BC, during the struggle for dominance in Thrace between the Seleucids, one of Alexander's successors, the Macedonians included the Romans. Meanwhile, in 188 BC, the Bizye (Vize) and the Astlar from the Demirköy region were among the four Thracian tribes that raided the Roman army at the mouth of the Maritsa River. While the Macedonians struggled to conquer inland Thrace, the Odrysians reemerged as a ruling tribe. In the 2nd century, some Thracian tribes sided with the Macedonians in the wars between Macedonia and Rome. With internal unrest intensifying, various tribes became influential in Thrace. By the end of the 2nd century, Rome's ascendancy over the Macedonians brought the Thracians closer to the Bithynians in northwestern Anatolia. Relations between Rome and the Thracians were marked by intense conflict in the 1st century BC. Among the Thracian tribes, which consisted of various tribes, there were some who were friendly with the Romans. However, the Romans were unable to achieve any decisive victory during this century. Thracian lands were left surrounded and autonomous.

While the Odrysians appeared to be friends of the Romans at the end of the 1st century BC, Khaimetalkes and his brother Rhaskuporis rose to prominence as Roman vassals in 7 AD. During this period of intense rebellion, they were tasked with suppressing these rebellions on behalf of Rome. These Sepeian kings, inheriting the inheritance of the Odrysian and Astian kings, were also at odds with each other. The fact that upon the death of Khaimetalkes, his son Kotys was given the southern part of Thrace distressed Rhaskuporis. Unsatisfied with the northern Thrace he inherited, Rhaskuporis had his nephew killed. He was killed by the Romans in Alexandria in 192 AD. The region, shaken by the Bessi rebellion of 11 AD, was rekindled in 21 AD by the freedom-loving Thracians. Anger at the Romans and their dependent Thracian rulers was immense. The Romans, driven by their desire to seize power directly, were unable to do much. The waves of rebellion that spread in 26 AD were suppressed. It is likely that the Thracian fortresses, built on high mountaintops with their natural fortifications—likely extensions of European Iron Age fortresses—provided an advantage to the rebels during the widespread rebellion. This location may have been a significant fortress, playing a significant role in the suppression of the great Thracian rebellion, where the Thracians who had sought refuge surrendered due to hunger and thirst. Some of the Thracians surrendered, while others chose to commit suicide. The fortresses described, due to their location and structure, match some of the fortresses around Demirköy. These fortresses are located in the İkiz Tepeler, Sislioba, and Sivriler regions. It is believed that these same fortresses were also used and repaired during the Genoese period.

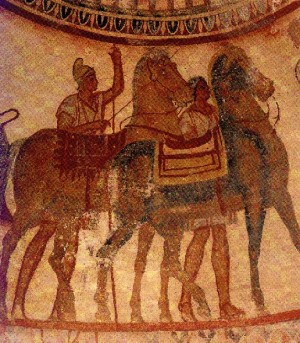

After the revolts were suppressed, Rhaimetalkes, the eldest son of Kotys of the Sapeians, was elected king in 38 AD, supported by Rome. Vize was the last surviving Thracian king outside of Dacia, and therefore the last capital of the Thracians, as evidenced by the Vize A Tumulus, which appears to have belonged to this king. When Rhaimetalkes was killed in 45 AD, the last remaining Thrace was annexed to Rome and became a province in 46 AD during the reign of Claudius (41-45 AD). The last Thracian traces persisted in remote mountainous regions north of the Strandja Mountains until the Middle Ages, before disappearing under the influence of Christianity.