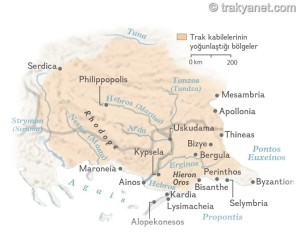

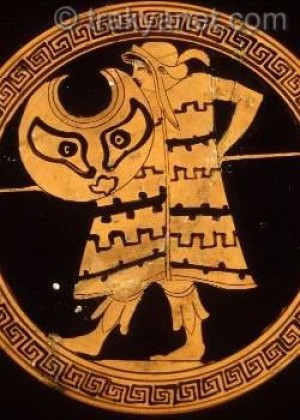

Thracians are the name we now give to the people who created one of history's oldest and most striking cultures, giving their name to the region we now call Thrace. While Thracian is not a term used by these people to describe themselves, it is now a valid term to describe this magnificent culture. Thracians are the creators of one of the most distinctive cultures in human history and have left us their immortal cultural legacy.

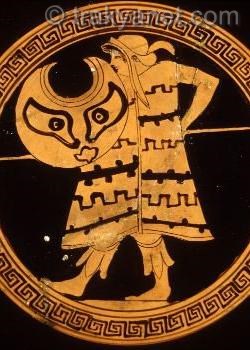

Today, the lands where the Thracians lived are shared by various Balkan nations. Thracian lands actually span a vast area, encompassing a large portion of the Balkans.

Türkiye and Bulgaria are among the countries that share the Thracian Heritage and are notable for the Thracian monuments within their borders.

The Thracians are one of the oldest Indo-European peoples who created civilization and lived in the area of the Dnieper and Dniester rivers, the southern slopes of the Carpathians, the Vardar, the northern Aegean coast and islands, and northwestern Anatolia. This populous society comprised a unified economic, social, behavioral, and cultural stereotype that was naturally integrated into the historical and geographical characteristics of the region. The Thracians lacked the characteristics of a nationality consistent with other ancient European ethnic groups. As early as the 5th century BC, Herodotus, the father of history, stated that they were the most diverse nation after the Indians and that if united, they would be invincible.

The formation of the Thracian ethnic structure is the result of millennia of interaction between the indigenous population and newcomers from the north. From the end of the Chalcolithic Age (5th-6th centuries) and the beginning of the Bronze Age (beginning of the 3rd century), archaeological materials indicate the movement of peoples between the southern slopes of the Carpathians, the Northern Black Sea steppes (southern Russia and Ukraine), and the Aegean-Black Sea region. However, this is not defined as a population change; rather, it is described as integration and active cultural interaction with newcomers alongside the natives.

The process of the formation of the Thracian ethnic structure, which lasted at least a millennium, did not witness radical changes or opposition among the people; on the contrary, it observed the preservation of traditions, access to new technological advancements, and the restructuring of society in a way that preserved their skills and knowledge. During this period, a special approach to the Universe and Nature, personified by the Supreme Goddess and the Sun God, emerged. Throughout their existence, the Thracians maintained contact with Minoan and Anatolian cultures and contributed to the formation of the Mycenaean civilization.

In the middle of the second millennium BC, changes took place in the Mediterranean world that would forever mark European history. The Minoan civilization disappeared under the pressure of the Achaeans, who were ruled by kings. The temporary name of the newly formed civilization was Mycenae (Mycenae), and it is the name of one of the most famous cities of this period. Dynastic lineages were the owners of new lands, with strongly fortified cities bordering them with citadels and palaces. The Achaeans were excellent soldiers, builders, skilled metallurgists, good shepherds, sailors, and even farmers. Piracy and plunder were commonplace during these years. At the same time, the Thracians emerged as a distinct Indo-European people. The Thracians were also ruled by kings. Their culture and civilization were typologically similar to the Achaeans. By the second half of the 2nd century BC, the Thracians were actively involved in the economic, political, and cultural life of Southeastern Europe and Western Anatolia. Their magnificent treasuries, scepters, sacred and fortified residences demonstrate that they were not inferior in power to the Achaean kings. In the mid-2nd century BC, the Thracian royal dynasties were still anonymous.

The end of the second millennium BC was marked by the Trojan War. This war is the first known war fought for control over the Dardanelles (Çanakkale) and the Bosporus. It is the war fought for the distribution of raw materials and markets, and is recounted in the poems "Iliad" and "Odyssey." In epic poetry, the Thracians emerged from anonymity; they are described as allies of the Trojans, equals to the Achaeans in bravery, valor, and wealth, and legendary Thracian kings such as Rhesos, Maron, Peiroos, and Akamas emerged. With the Trojan War, from the beginning of the 1st century BC onward, significant socio-economic and political changes began for the Greeks, leading to the demise of the Mycenaean civilization and the emergence of city-states. In Thrace, however, society still follows the Mycenaean pattern, and the economy is organized in the same way. Kingdoms are ruled by dynastic lineages headed by kings, who, followed by aristocrats and cavalry, exert their authority over vast territories. Peasants are free and organized into regional rural communities. A royal monopoly over mining, metallurgy, and the production of metal products is maintained. The treasury and workshops for the production of precious metals are located near the royal headquarters.

Thracian rulers did not have a capital. The capital was the ruler's residence. Numerous political and religious centers and fortified residences, operating during different historical periods, have been documented in ancient Thrace, where political and religious authority was exercised. For example, the Odrysian Kingdom was ruled by paradynasts—members of the royal family who ruled over large areas in the king's name for a specific period. Paradynasts often attempted to gain independence or seize the throne. The most famous paradynast is Seuthes (I. Seuthes), whose soldiers and the ancient Greek historian Xenophon left us a description of the royal residence and life.

Later, state institutions became more prominent in Thrace, and data and information about these states are generally not based on legend. Among all the countries located in Thrace, a few, as dynastic families, took their place in pre-Roman European history. According to scribes and archaeological evidence, the Getae settled on both sides of the Danube's lower course. West of the Oskios River (present-day Iskar), in what is now northwestern Bulgaria and northeastern Serbia, lies the Thrace of the Triballoi. The Bessi lived in the Rhodope Mountains and the northern pre-mountain foothills. According to Homer's "Iliad," the Edones, known for their king Rezos, inhabited the area downstream of the Struma River, whose center was Mount Pangaion, rich in gold and silver deposits.

The Dolonkoi and their northern neighbors, the Apsinthioi, inhabited the Thracian Chersones (today's Gallipoli Peninsula). Their territory extended downstream of the Hebros (today's Maritza/Meriç) River and downstream to the Agrianes (today's Ergene) River. The Dolonkoi sent an envoy to the Pythia Oracle at Delphi to learn how to deal with the Apsinthioi. Following the predictions, they contacted Miltiades the Elder, a former Athenian from the Philae family. Following the negotiations, an agreement was reached, and he was granted royal honors. Thus, in 561-560 BC and 556 BC, the Thracians and Athenians formed states. The Athenian historian Thucydides (5th century BC) reports that the Odrysian kingdom was the largest state in Europe between the Adriatic and the Black Seas. The borders of the Odrysaese Ethnonym include the area from the Rhodope, Sakar and Istranca mountains, with ancient Greek colonies in the Aegean, Marmara and Black Seas, from the upper reaches of the Tonzos (today's Tunca) River to the mouth of the Hebros (today's Maritza/Meriç) River.

The Odrysian State first appears in Greek writers during the reign of King Teres. Teres, through his skillful policies, capitalized on the Persian King Darius I Dariusprez's march against the Scythians, passing through Eastern Thrace, the Balkan Mountains, and the Danube River. The Achaemenid dynasty began expanding its territory during the Persian Empire's Achaemenid Empire (519/514/512 BC), aiming to include the entire Black Sea basin within its borders. After his unsuccessful campaign, the "king of kings" retreated from north to south, finding a starting point in the region of the Sea of Marmara and the Straits. There, Teres exploited the military and political vacuum created around the Haemus Mountains, which had been lashed from the north. He recruited the Getae, who felt the Persians' blow, and in the 80s of the 5th century BC, he reached the lower reaches of the Danube River, defining the river as the northern border of his kingdom. The borders extended southeastward to Byzantium (present-day Istanbul). This occurred after the Persians withdrew from the Propontis (today's Sea of Marmara) and the Aegean Sea, and from the coasts at the mouths of the rivers. That is, after their losses at Plataia, and their expulsion from Sestos between 479 and 478 BC, the Teres moved towards the Thracian delta – the area between Salmydessos (present-day Kıyıköy on the Black Sea in European Türkiye) and Byzantium. The entry into the Thynoi's territory was carried out by warlike Thracians, known for their skillful night fighting, and the battle resulted in heavy losses. Despite their large numbers, many of their soldiers were killed in action, and all the rest were captured and held captive.

It is likely that not only the difficulties Teres I faced in establishing power over the Thynoi, but also the persistent hostility shown by the inhabitants of Strandzha, later led Seuthes II to take special precautions for his nighttime security. According to Xenophon, he would approach his camp with fires around which no one was present. This way, the guards working in the dark at night could see who was coming, but they remained invisible. The tower where the king resided was protected by a circle of guards around it. During the day, they grazed freely, and at night, they maintained their safety by preparing for riding.

The lands he conquered between the Propontida and the Gulf of Burgaz were later transformed into the Parahanedar Sanjak and the strategic Astika. Before seizing the Thracian delta, he conquered the lands downstream of the Agrianes River (the modern-day Ergene River in European Türkiye). After the Athenians repelled the Persians from Doriskos to the mouth of the Hebros River (modern-day Maritza/Meriç) in 465/464 BC, the areas downstream remained under his control.

Messages sent to Teres' sons, Sparadokos (464 BC - 444 BC) and Sitalkes (444 BC - 424 BC) have been found. At that time, the Odrysian Kingdom was a triangle with a main line extending from the mouth of Mesta in the Aegean Sea to the mouth of the Danube in the Black Sea. Evidence of the power of the Odrysian royal dynasty is the Odrysian treasury, the largest of which is worth 1,000 talents, or 260,000 kg of metal products and coins.

Sitalkes took advantage of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431-404 BC) and, with an army of 150,000 men, attempted to conquer Eastern Macedonia and the Chalkidiki peninsula, but failed to hold on to these territories. He died after a battle with the Triballis for the northwestern part of the Odrysian kingdom, and his successor, Seuthes I (424-407/405 BC), began his expansion into the Thracian Chersonese (today's Gallipoli peninsula), aiming to conquer it and then establish control over the sea routes from the Black Sea, supplied with Thracian and Scythian wheat, to Athens.

Kotys I (383–359 BC), a tireless soldier, a two-faced diplomat, and a harsh ruler, was assassinated by Athenian assassins during a banquet at one of Philip II's coastal residences in the year he was proclaimed King of Macedonia. His death brought an end to the fierce war between Athens, which defended its conquests in the Thracian Chersonese for the protection of its sea lanes, and Kotys, whose plans were far more ambitious than they were.

Philip of Macedon, with the best army of the time, launched his expansion east of the Struma River. With Kotis dead, Odrysian Thrace was divided into three parts. After his successful conquests in the south, Philip deposed two of the kings and, in the 40s of the 4th century BC, conquered the core of the Odrysian realm, ruled by Kotis I's son, Kersebloptes (359–341 BC). The Macedonian army advanced along the slopes of the Hebros (present-day Maritza/Meriç) River and the Tonzos (present-day Tunca) River, reaching the Kabyle Odrysian kingdom (near the present-day town of Yambol in southern Bulgaria) and Pulpudeva (Philippopolis, present-day Plovdiv), the city of the seven hills.

Macedonian dominance in Thrace is explained by the presence of only a few garrisons. During Alexander's lifetime, Seuthes III (330-302/301 or 297 BC) maintained complete autonomy in Thrace and its official rulers after his death in 323 BC. After Alexander's death (323 BC), Lysimachus (322-28 BC) inherited Thrace from the neighboring nations along the Pontus. He succeeded in establishing military and political control only on the Propontis and the coast of the Thracian Chersonese and partially on the northern coast of the Aegean. East of the western coast of Pontus, the diadoch controlled only a portion from the coast of present-day Strandzha to Salmydessos. The dispute with Seuthes III remained unresolved. The lands ruled by Seuthes and Sparatokos extend from the upstream to the lower stream of the Tunca River and include the Sakar Mountain.

The Odrysian state managed to resist the Celtic invasion that began in Central Europe in the 280-279 BC and reached the southeast in the 3rd century BC. Celtic groups maintained their rule in Thrace until the 20s of the 3rd century BC, when it was destroyed by the Thracians.